History, at first glance, seems like a straightforward recounting of facts: dates, events, names. But peel back the surface, and history reveals itself as a living narrative—one that can be shaped, twisted, or polished depending on who writes it and why. History guides, whether textbooks, documentaries, or museum placards, are not neutral vessels. They are curated lenses, selectively highlighting certain events, heroes, or tragedies while downplaying others. The question arises: are these guides shaping our understanding in a balanced way, or are they subtly embedding bias under the guise of education?

The Craft of Historical Storytelling

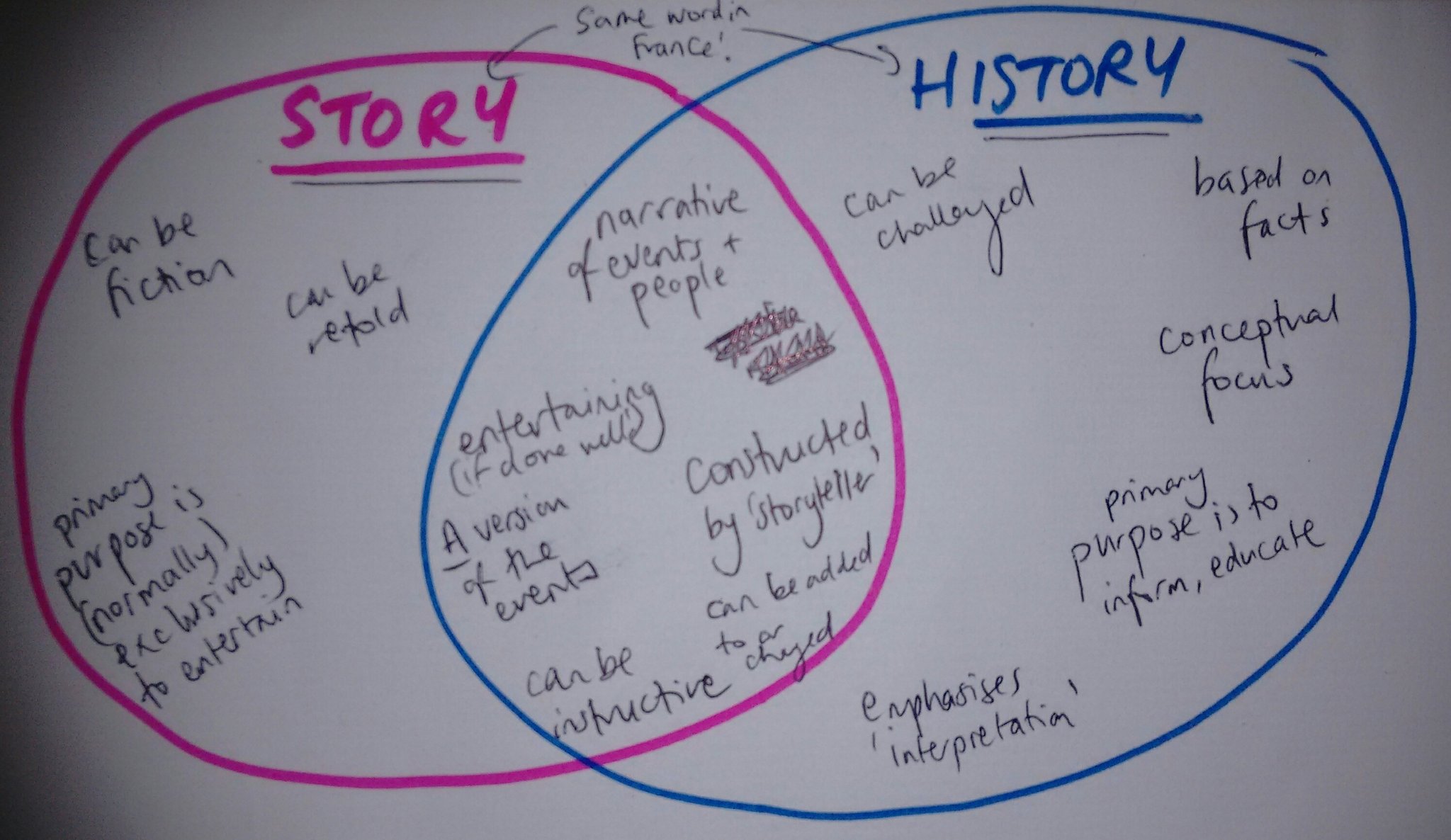

Human beings are natural storytellers. From cave paintings to social media timelines, we organize experiences into narratives. History guides do the same, but with added layers of authority: authors, peer reviews, and institutional endorsements. A well-crafted guide doesn’t just list facts; it frames them. Consider a textbook describing the Industrial Revolution. One guide might celebrate it as the dawn of technological progress and modern civilization. Another might emphasize worker exploitation, child labor, and environmental degradation. Both are factually correct, yet the emphasis completely shifts a reader’s moral and emotional takeaways.

The framing of history is as important as the content itself. Cognitive scientists explain that humans are highly susceptible to narrative bias. We naturally assign meaning and moral weight to stories, often more than to raw data. Thus, a history guide that selects what to highlight, omit, or dramatize is doing more than educating—it is shaping perspective.

National Identity and the Politics of Memory

History guides often intersect with national identity. Governments and educational institutions have long recognized that the way history is taught affects collective memory. For instance, postcolonial nations may emphasize narratives of resistance and liberation, while former colonial powers might highlight economic or cultural “achievements.” These contrasting presentations do more than convey facts—they nurture pride, guilt, or even resentment across generations.

Bias in history is rarely blatant. It’s subtle, embedded in choices of language, imagery, and structure. Words like “discovery” versus “invasion” carry weight. Chronological choices—what gets included, what gets glossed over—also influence perception. For example, in some Western textbooks, the colonization of the Americas is framed as an era of exploration and civilization, while in others, it is portrayed as conquest and displacement. Both accounts are rooted in fact, yet they evoke radically different emotional responses.

The Role of Omission

Omission is as powerful as inclusion. When history guides skip events, communities, or viewpoints, they silence entire perspectives. Imagine a world history guide that glosses over the contributions of women scientists or artists. Readers may unconsciously internalize the idea that innovation is primarily male-driven. Similarly, leaving out certain ethnic or indigenous narratives can reinforce systemic marginalization. The absence of information is a subtle form of bias, often invisible to the casual reader.

Even within well-documented topics, selective omission matters. For instance, textbooks discussing World War II might prioritize European theaters while briefly mentioning or neglecting the suffering in Asia or Africa. The choices about what is considered “central” history shape which stories are remembered—and which fade into obscurity.

Emotional Resonance and Cognitive Framing

Humans are wired to respond emotionally to stories. History guides frequently harness this instinct. Case studies, personal letters, or dramatic imagery can make history feel immediate and visceral, but they also guide emotional interpretation. An anecdote about a heroic soldier or a suffering civilian can anchor broad historical trends in human experience—but it can also skew perception, emphasizing individual narratives over systemic analysis.

Cognitive framing occurs not only in storytelling but also in visual presentation. Maps, photographs, and timelines are powerful tools that guide understanding, often subtly. A map showing territorial expansion of one nation might evoke pride or fear, depending on context and color choices. Similarly, graphs of economic growth can suggest progress while omitting social inequities. Visual framing is an underappreciated yet potent avenue for shaping perspective.

Textbook Economics: Market Forces and Bias

History guides are not only educational—they are commodities. Publishers compete for schools and markets, and this competition affects content. Simplified narratives sell better than nuanced, complex ones. Textbooks often aim for clarity and memorability, sometimes at the expense of accuracy. This commercial influence can introduce a form of bias: the “storyline bias,” where history is packaged to appeal to dominant societal narratives rather than to challenge or complicate them.

Moreover, political pressure can shape content. In some countries, textbooks are vetted by government authorities to align with national ideology. This creates a feedback loop: official narratives shape guides, which shape public perception, which reinforces official narratives. The result is a subtle but persistent shaping of collective memory and identity.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Comparing history guides from different countries reveals striking contrasts. The same event can be presented in radically different ways, reflecting local values, politics, and identity. Consider the Cold War: Western guides may focus on the fight against communism and the triumph of democracy, while Russian guides might highlight Western aggression and ideological threats. Neither account is fully “wrong,” yet each conveys a selective moral lesson.

Globalization and the internet have complicated this dynamic. Students now have access to multiple perspectives, challenging single-narrative guides. Yet the tension between authoritative guides and diverse sources persists. Who gets to define “accurate history” remains a pressing question.

Digital History Guides: New Opportunities, New Biases

The rise of digital history resources has transformed access and presentation. Interactive timelines, online archives, and multimedia guides can enrich understanding. However, digital platforms introduce algorithmic bias. Search engines and recommendation systems may amplify certain narratives while marginalizing others. The way digital content is structured—clickable modules, curated playlists, trending stories—shapes both what is learned and how it is perceived.

Digital guides also allow for user-generated content, which is a double-edged sword. On one hand, this democratizes historical storytelling, giving voice to underrepresented perspectives. On the other, it increases the risk of misinformation, cherry-picked facts, and emotionally manipulative narratives. In this environment, perspective and bias are often inseparable.

Strategies for Critical Engagement

If history guides inherently shape perspective, what can students and readers do? Critical engagement is key. Readers should:

- Compare multiple sources: Contrasting guides from different countries, publishers, or ideological viewpoints helps reveal selective emphasis.

- Examine framing choices: Look at language, images, and story order. Who is the hero? Who is omitted?

- Investigate omissions: Ask what is missing. Which voices or events are absent?

- Understand the creator: Consider the author, publisher, and institutional context. What might influence their choices?

- Question emotional cues: Reflect on why certain events are highlighted for emotional impact. Does this shape judgment?

Critical thinking transforms guides from passive instruction to active exploration, reducing the risk of internalizing bias unconsciously.

The Paradox of Historical Authority

Here lies the paradox: history guides aim to educate, yet they are inevitably subjective. Complete neutrality is impossible because every selection, word, and illustration is a choice. The question is not whether guides shape perspective—they clearly do—but whether they cultivate critical, informed perspectives or subtly impose bias. The difference lies in transparency and engagement. Guides that acknowledge multiple viewpoints, highlight uncertainty, and invite reflection foster informed understanding rather than indoctrination.

Conclusion: Navigating Between Perspective and Bias

History guides are both windows and mirrors: they show us the past, but also reflect contemporary values, priorities, and ideologies. They are tools that shape not only what we know, but how we feel and think about it. Recognizing this dual role is crucial. By approaching guides with curiosity, skepticism, and empathy, readers can appreciate the richness of history while resisting unexamined bias.

Ultimately, history is less about finding a single “truth” and more about understanding the complex interplay of fact, narrative, and interpretation. Guides shape perspectives, yes—but awareness, critical thinking, and multiple viewpoints are shields against unintentional indoctrination. The challenge—and the excitement—lies in navigating between perspective and bias, learning not only what happened, but why and how it is remembered.