A Quiet Revolution on the Wrist

Mental health crises rarely announce themselves with clarity. They tend to emerge gradually—through subtle changes in sleep, energy, focus, and emotional balance—long before reaching a breaking point. For decades, these early signals have been easy to miss, both for individuals and for clinicians. Today, however, a quiet technological revolution is taking place on our wrists, in our pockets, and even in our clothing. Wearable devices—once simple step counters—are evolving into sophisticated biosensing platforms. The question is no longer whether they can track physical activity, but whether they can help anticipate mental health crises before they escalate.

This article explores that question in depth. We will examine how wearables collect data, what kinds of signals are relevant to mental health, how prediction models work, and where the limits lie. We will also look at ethical considerations, design challenges, and what the future might hold. Throughout, the goal is not hype, but clarity: what wearables can realistically do, what they cannot, and why the distinction matters.

Understanding Mental Health Crises: Patterns Before the Storm

A mental health crisis is not a single event; it is a process. While experiences differ widely, many crises are preceded by identifiable changes in physiology and behavior. These changes may include disrupted sleep cycles, increased physiological stress, social withdrawal, reduced physical activity, or sudden spikes in restlessness.

Traditionally, detection relies on self-reporting or observation by others. Both methods are limited. People often normalize their own distress, delay seeking help, or lack the vocabulary to describe what they are experiencing. Clinicians, meanwhile, typically see patients only intermittently, relying on retrospective accounts that may be incomplete or biased.

Wearables offer a different approach: continuous, passive, and objective monitoring. They do not replace clinical judgment, but they can fill in the gaps between appointments and capture patterns that are otherwise invisible.

What Modern Wearables Actually Measure

To understand predictive potential, we first need to understand the data itself. Modern wearables collect far more than step counts. Key categories include:

Physiological Signals

- Heart Rate (HR): Average heart rate, resting heart rate, and fluctuations over time.

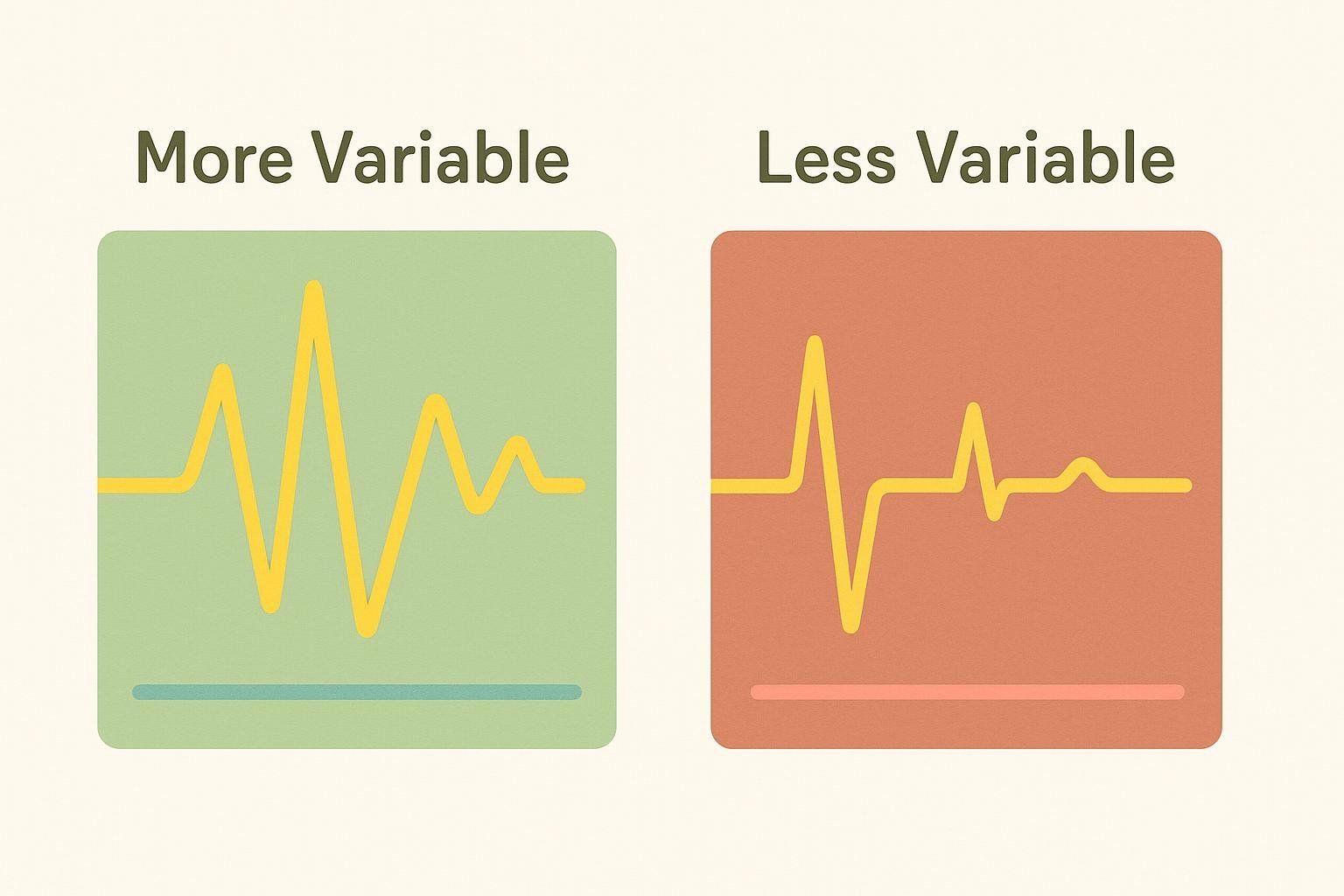

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV): Variations in time between heartbeats, often associated with stress regulation and autonomic nervous system balance.

- Skin Temperature: Subtle changes linked to circadian rhythms and stress responses.

- Electrodermal Activity (EDA): Changes in skin conductance related to arousal and emotional intensity.

- Respiratory Rate: Breathing patterns during rest and sleep.

Behavioral Signals

- Sleep Duration and Quality: Sleep stages, awakenings, and regularity.

- Physical Activity: Intensity, frequency, and variability of movement.

- Sedentary Time: Extended periods of inactivity.

- Daily Rhythms: Consistency of routines across days.

Contextual and Environmental Signals

- Location Patterns: Stability or fragmentation of daily locations.

- Social Proxies: Communication frequency or device interaction patterns (when available).

- Light Exposure: Relevant to circadian alignment.

Individually, these signals are not diagnostic. Collectively, and over time, they form a behavioral and physiological signature that can reflect mental state changes.

From Raw Data to Insight: How Prediction Models Work

Data alone does not predict anything. Prediction emerges through interpretation, typically using statistical and machine learning models. These models do not “understand” mental health in a human sense; they detect patterns and deviations.

Baseline Establishment

Prediction depends on personalization. A heart rate of 80 beats per minute may be normal for one person and elevated for another. Wearable-based systems usually begin by learning an individual’s baseline over weeks or months.

This baseline includes:

- Typical sleep duration and timing

- Normal ranges of activity

- Usual stress-response patterns

Crises are not detected by absolute thresholds, but by deviations from personal norms.

Trend Detection

Rather than reacting to single-day anomalies, predictive models focus on trends:

- Gradual sleep reduction over multiple nights

- Increasing physiological arousal during rest

- Loss of daily rhythm regularity

- Decreased recovery after stress

These trends are often more informative than dramatic spikes.

Multimodal Integration

The most promising approaches integrate multiple data streams. For example:

- Reduced sleep + elevated resting heart rate

- Lower activity + increased physiological stress markers

- Irregular routines + heightened nighttime arousal

When several signals shift together, confidence increases that something meaningful is happening.

What “Prediction” Really Means in Mental Health

The word “predict” can be misleading. In this context, prediction does not mean foreseeing a specific event at a specific time. Instead, it means estimating increased risk.

A more accurate framing is early risk signaling:

- Identifying periods when someone may be more vulnerable

- Flagging changes that warrant attention or support

- Providing prompts for reflection or check-ins

This distinction is crucial. Wearables are not crystal balls; they are trend detectors.

Evidence of Feasibility: What Research Has Shown So Far

Across academic and applied research, several consistent findings have emerged:

- Sleep disruption is one of the strongest early indicators of mental health deterioration.

- Reduced HRV is often associated with chronic stress and emotional dysregulation.

- Behavioral withdrawal, reflected in lower activity and reduced routine regularity, often precedes worsening mental states.

- Circadian rhythm instability correlates with mood instability and cognitive strain.

Importantly, these indicators are not disorder-specific. They do not diagnose conditions; they reflect stress on regulatory systems shared across many forms of distress.

Strengths of Wearables in Mental Health Monitoring

Continuous and Passive Data Collection

Unlike questionnaires, wearables do not rely on memory or motivation. They capture data during everyday life, including during sleep.

Early Detection Potential

Subtle changes can be detected weeks before a person consciously recognizes a problem.

Personalization at Scale

Algorithms can adapt to individuals rather than forcing everyone into the same normative framework.

Empowerment Through Awareness

When designed well, feedback from wearables can help users notice patterns and make informed adjustments to routines, sleep, or stress management.

Limitations and Risks: Where Wearables Fall Short

Despite their promise, wearables are not a magic solution.

Ambiguity of Signals

The same physiological change can have many causes. Elevated heart rate may reflect excitement, illness, or stress. Context matters, and context is often missing.

False Positives and Negatives

Overly sensitive systems may generate unnecessary alerts, while conservative systems may miss meaningful changes. Striking the right balance is difficult.

Data Quality Issues

- Inconsistent wear

- Sensor inaccuracies

- Battery limitations

- Variability across devices

Poor data can lead to misleading conclusions.

Psychological Impact

Constant monitoring can increase anxiety for some users, especially if feedback is poorly framed.

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

Mental health data is among the most sensitive information a person can share. Wearables raise significant ethical questions.

Data Ownership

Who owns the data: the user, the device manufacturer, or a third-party service?

Consent and Transparency

Users must understand what is being collected, how it is used, and what inferences are being made.

Risk of Misuse

Employers, insurers, or institutions could misuse mental health-related data if safeguards are not robust.

Autonomy and Agency

Predictive systems should support, not override, individual decision-making.

Ethical design is not optional; it is foundational.

Clinical Integration: Support, Not Replacement

Wearables are most effective when integrated into broader care systems.

Augmenting Clinical Insight

Longitudinal data can help clinicians:

- Understand symptom trajectories

- Evaluate treatment responses

- Identify early warning signs

Bridging Gaps Between Visits

Wearables can provide context between appointments, especially for individuals with limited access to care.

Avoiding Overreliance

No algorithm should replace professional judgment or human connection. Wearables are tools, not arbiters.

Design Matters: How Feedback Is Presented

The way information is communicated can determine whether a wearable helps or harms.

From Alerts to Insights

Binary alerts (“risk detected”) can be alarming. Trend-based summaries and reflective prompts are often more constructive.

Emphasizing Agency

Language should encourage curiosity and self-care, not fear or fatalism.

Customization and Control

Users should be able to adjust:

- Sensitivity levels

- Types of feedback

- When and how notifications appear

Good design respects psychological diversity.

Cultural and Social Contexts

Mental health is shaped by culture, environment, and social norms. Predictive models trained in one population may not generalize to another.

Factors that influence interpretation include:

- Work schedules

- Family structures

- Social expectations

- Climate and seasonal patterns

Responsible systems must account for diversity, not erase it.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence

AI is central to wearable-based prediction, but its role is often misunderstood.

Pattern Recognition, Not Understanding

AI detects correlations, not causes. Human oversight is essential for interpretation.

Transparency and Explainability

Black-box predictions undermine trust. Users and clinicians need understandable explanations of why signals change.

Continuous Learning

Models must adapt over time as individuals’ lives and bodies change.

Future Directions: What the Next Decade May Bring

Looking ahead, several developments are likely:

- Improved sensors capable of capturing richer emotional and physiological signals

- Better personalization through adaptive learning models

- Integration with digital therapeutics, such as guided interventions

- Stronger privacy frameworks and on-device processing

- Cross-platform ecosystems linking wearables, smartphones, and clinical systems

The future is less about prediction alone and more about supportive ecosystems.

A Balanced Answer to a Complex Question

So, can wearables predict mental health crises?

They can identify patterns associated with increased risk. They can detect early warning signs. They can support awareness, monitoring, and timely intervention. What they cannot do is replace human judgment, eliminate uncertainty, or guarantee prevention.

Their greatest value lies in partnership—with users, clinicians, and ethical frameworks guiding their use.

Mental health crises are deeply human experiences, shaped by biology, psychology, and environment. Wearables offer a new lens, not a final verdict. When used thoughtfully, that lens can help us see earlier, respond sooner, and care more effectively.

Final Reflection: Technology with Humility

The promise of wearables in mental health is not about prediction as control. It is about prediction as care—about noticing when something is changing and responding with curiosity rather than alarm.

In that sense, the most important feature of any wearable is not the sensor or the algorithm, but the intention behind its use. Technology can amplify awareness, but only humans can transform awareness into understanding and support.